(Didn’t catch Part I? Read it first!)

(Didn’t catch Part I? Read it first!)

From the city of Rome, New York, came a strongly worded letter from a citizens’ group that said it wasn’t Upham who wrote the Pledge, but a clergyman named Francis Bellamy (sometimes called Frank) who used to preach in that part of the country!

Margarette threw up her hands. Here was the Bellamy claim again, only this time dressed up in a minister’s suit of cloth. But wasn’t it strange that the youthful plagiarist grew up to be a man of God?

Then came a more disturbing letter. It was from a David Bellamy in Rochester, New York, who identified himself as the son of the late Reverend Bellamy. He said that he clearly remembered his father writing the Pledge of Allegiance after leaving his pulpit in Rome, New York, to work for The Youth’s Companion!

Margarette was deeply troubled. In her research on Bellamy, she had found no mention of a journalistic career, much less a ministerial one. But the really strange part was this: If the new information was correct, then Bellamy worked on the same magazine from which he allegedly pilfered the Pledge in order to win a school contest! It seemed fantastic.

The lights burned late on Portsmouth’s Hatton Street as Margarette pored over her newly thickened Bellamy file. The contradictions had grown. Bellamy was born in Kansas; he was born in New York. He served in the Spanish-American War; he did not serve in that war. He died in Colorado in 1915; he was seen in

Florida in 1929. Margarette wondered for a giddy moment if Bellamy had led a bizarre double life. She finally put out the light, but slept only fitfully.

At about 4 o’clock in the morning, she sat bolt upright in bed, her mind ablaze with sudden clarity. She knew now that there were two Frank Bellamys, and that they were unrelated. One was the Kansas “schoolboy” who stole the Pledge of Allegiance out of a magazine to win a contest. The other was the preacher from Rome, New York, who worked on The Youth’s Companion. It would, of course, be this second Bellamy who wrote the Pledge for which his boss, James B. Upham, took credit.

Now Margarette was sure she had the right solution, but even the best detective must take his case to court. Her court was the United States Flag Association, a private sector group that sets standards for honoring and displaying the American flag. At Margarette’s request, they chose three outstanding historians to sift through the evidence. Months later, Margarette received their final report, which boiled down to this:

In 1891 the country was a beehive of activity in preparation for the next year’s celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in America. The Youth’s Companion was eager to take part. James B. Upham, an executive of the magazine, proposed that The Youth’s Companion sell flags, at cost, to schools

throughout the United States. His goal was a flag in front of every schoolhouse in America. And wouldn’t it be wonderful if on Columbus Day all the school children in the land recited a pledge to their newly acquired flags!

The job of writing the Pledge went to editor-writer Francis Bellamy, a former preacher from Rome, New York, known in his youth as Frank. It was published in the September 8th, 1892 issue of The Youth’s Companion without a byline as all staff-written articles were. No one saw any reason to make an exception in the case of the Pledge of Allegiance. No one imagined it would be used or remembered beyond that one Columbus Day in 1892.

But used it was. And used, and used. And plagiarized by the other Frank Bellamy. Was the similarity of names a coincidence? Certainly, but one that worked for the plagiarist. Programs of Columbus Day events containing the Pledge and Francis Bellamy’s name as a committee member were in fact distributed at festivals. How easy for the Kansas “schoolboy” to point to the Bellamy name, and say, “That’s me.”

In years that followed changes were made in the Pledge.

The phrase “my flag” was changed to “the flag of the United States of America.” Thus an expression of personal love was exchanged for a pledge of loyalty to government. Francis Bellamy opposed the change, but no one paid any attention to him. The change was made by a group of patriotic organizations that felt no need to consult with Bellamy; they believed that James B. Upham, executive of the Youth’s Companion, was the true author.

An act passed by Congress in 1942 made the Pledge of Allegiance, for the first time, the official Pledge of the United States. It was not until the 1950’s, at the height of the Cold War, that Congress voted to insert the phrase “under God,” no doubt to prove to the world that we were different from the atheistic Soviet Union.

Francis Bellamy died in 1931, still struggling to achieve recognition for his creation, not knowing that five years after his death a young woman in Portsmouth, Virginia would take up the battle, and win.

Margarette Miller died in 1984, secure in the knowledge that her solution to the mystery of the unsigned Pledge had been upheld by the Library of Congress and by every state legislature in the United States.

How fitting for this American story that the two leading characters in it are a Christian minister and a Jewish woman who brought his authorship to light.

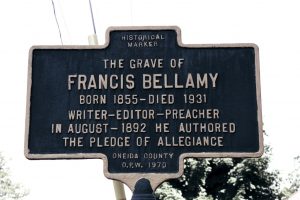

Bellamy’s gravesite in Rome, New York is now adorned with a white granite monument and a plaque that attributes the creation of those 23 original words to him.

The author of our Pledge of Allegiance is not lying in an unmarked grave.

Jerome Coopersmith has authored more than 100 television scripts for anthology dramas, episodic series and television movies and specials. His Broadway musical, Baker Street, based on the stories of Sherlock Holmes, earned him a Tony Nomination. He is a longstanding and much appreciated member of Mystery Writers of America.

Jerome Coopersmith has authored more than 100 television scripts for anthology dramas, episodic series and television movies and specials. His Broadway musical, Baker Street, based on the stories of Sherlock Holmes, earned him a Tony Nomination. He is a longstanding and much appreciated member of Mystery Writers of America.